About the abdominal muscles

External Oblique

The abdominal external oblique muscle (also external oblique muscle, or exterior oblique) is the largest and outermost of the three flat abdominal muscles of the lateral anterior abdomen. The external oblique functions to pull the chest downwards and compress the abdominal cavity, which increases the intra-abdominal pressure as in a valsalva maneuver. It also performs ipsilateral (same side) side-bending and contralateral (opposite side) rotation. So the right external oblique would side bend to the right and rotate to the left. The internal oblique muscle functions similarly except it rotates ipsilaterally.

Source

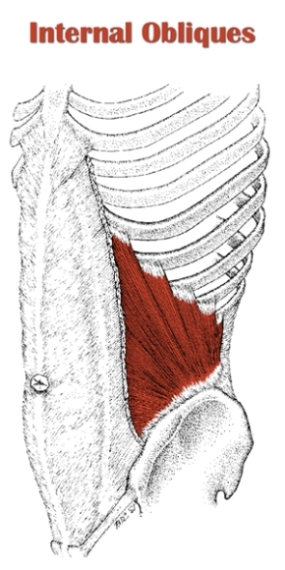

Internal Oblique

The abdominal internal oblique muscle, also internal oblique muscle or interior oblique, is an abdominal muscle in the abdominal wall that lies below the external oblique muscle and just above the transverse abdominal muscle. The internal oblique performs two major functions. Firstly as an accessory muscle of respiration, it acts as an antagonist (opponent) to the diaphragm, helping to reduce the volume of the chest cavity during exhalation. When the diaphragm contracts, it pulls the lower wall of the chest cavity down, increasing the volume of the lungs which then fill with air. Conversely, when the internal obliques contract they compress the organs of the abdomen, pushing them up into the diaphragm which intrudes back into the chest cavity reducing the volume of the air-filled lungs, producing an exhalation.

Secondly, its contraction causes ipsilateral rotation and side-bending. It acts with the external oblique muscle of the opposite side to achieve this torsional movement of the trunk. For example, the right internal oblique and the left external oblique contract as the torso flexes and rotates to bring the left shoulder towards the right hip. For this reason, the internal obliques are referred to as "same-side rotators."

Source

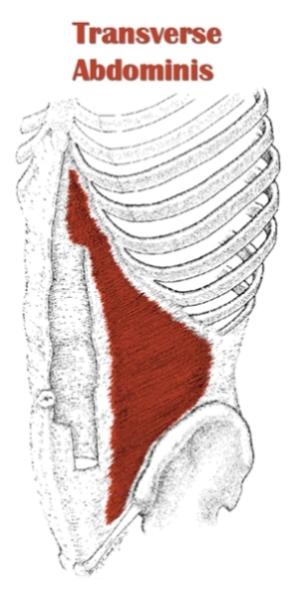

Transversus Abdominis

The transverse abdominal muscle (TVA), also known as the transverse abdominis, transversalis muscle and transversus abdominis muscle, is a muscle layer of the anterior and lateral (front and side) abdominal wall which is deep to (layered below) the internal oblique muscle. It is thought by most fitness instructors to be a significant component of the core.The transverse abdominal helps to compress the ribs and viscera, providing thoracic and pelvic stability. This is explained further here. The transverse abdominal also helps a pregnant woman to deliver her child. Without a stable spine, one aided by proper contraction of the TVA, the nervous system fails to recruit the muscles in the extremities efficiently, and functional movements cannot be properly performed.[2] The transverse abdominal and the segmental stabilizers (e.g. the multifidi) of the spine have evolved to work in tandem.

While it is true that the TVA is vital to back and core health, the muscle also has the effect of pulling in what would otherwise be a protruding abdomen (hence its nickname, the “corset muscle”). Training the rectus abdominis muscles alone will not and can not give one a "flat" belly; this effect is achieved only through training the TVA.[3] Thus to the extent that traditional abdominal exercises (e.g. crunches) or more advanced abdominal exercises tend to "flatten" the belly, this is owed to the tangential training of the TVA inherent in such exercises. Recently the transverse abdominal has become the subject of debate between biokineticists, kinesiologists, strength trainers, and physical therapists. The two positions on the muscle are (1) that the muscle is effective and capable of bracing the human core during extremely heavy lifts and (2) that it is not. Specifically, one recent systematic review has found that the baseline dysfunction of TVA cannot predict the clinical outcomes of low back pain.[4] Similarly, another systematic review has revealed that the changes in TVA function or morphology after different nonsurgical treatments are unrelated to the improvement of pain intensity or low back pain related-disability.[5] These findings have challenged the traditional emphasis of using TVA-targeted intervention to treat low back pain.

Source

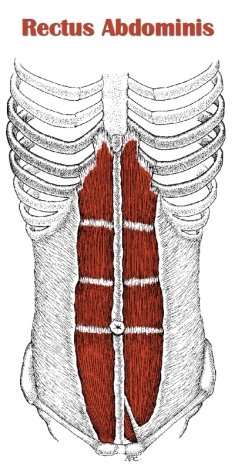

Rectus Abdominis

The rectus abdominis muscle, also known as the "abdominal muscle", is a paired muscle running vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the human abdomen, as well as that of some other mammals. There are two parallel muscles, separated by a midline band of connective tissue called the linea alba. It extends from the pubic symphysis, pubic crest and pubic tubercle inferiorly, to the xiphoid process and costal cartilages of ribs V to VII superiorly.[1] The proximal attachments are the pubic crest and the pubic symphysis. It attaches distally at the costal cartilages of ribs 5-7 and the xiphoid process of the sternum.

The rectus abdominis muscle is contained in the rectus sheath, which consists of the aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal muscles. Bands of connective tissue called the tendinous intersections traverse the rectus abdominis, which separates this parallel muscle into distinct muscle bellies. The outer, most lateral line, defining the "abs" is the linea semilunaris. In the abdomens of people with low body fat, these muscle bellies can be viewed externally and are commonly referred to as "four", "six", "eight", or "ten packs", depending on how many are visible; although, six is the most common.

The rectus abdominis is an important postural muscle. It is responsible for flexing the lumbar spine, as when doing a so-called "crunch" sit up. The rib cage is brought up to where the pelvis is when the pelvis is fixed, or the pelvis can be brought towards the rib cage (posterior pelvic tilt) when the rib cage is fixed, such as in a leg-hip raise. The two can also be brought together simultaneously when neither is fixed in space.

The rectus abdominis assists with breathing and plays an important role in respiration when forcefully exhaling, as seen after exercise as well as in conditions where exhalation is difficult such as emphysema. It also helps in keeping the internal organs intact and in creating intra-abdominal pressure, such as when exercising or lifting heavy weights, during forceful defecation or parturition (childbirth).

Source

Pyramidalis

The pyramidalis muscle is a small triangular muscle, anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle, and contained in the rectus sheath. The pyramidalis, when contracting, tenses the linea alba.

Source

Exercises

Stretches

- Cobra Pose

- Lay face down on the floor or an exercise mat. This is your starting position.

- With your hips flat on the ground, push your upper body upward, while looking straight ahead. This will stretch the abdominal muscles.

- Hold the position for 20 seconds, then return to the starting position

- Cat-Cow stretch

- Get on your hands and knees, and tuck your head downward as you arch your back, similar to how a cat does it.

- Extend the neck all the way upwards, and drop your belly all the way downwards, stretching the abdominal muscles.

- Hold for 20 seconds, then return to the starting position.

- Seated Side-Straddle stretch

- Sit upright on the floor with your legs apart.

- Raise your arms to the side with your elbows bent and fingers pointing up.

- Engage the abdominal muscles and slowly bend sideways to the right, bringing the right elbow towards the floor. Don’t bend forward or rotate. You should feel the stretch through the obliques.

- Hold this position for 15 to 30 seconds, then return to the starting position. Repeat on the left side and hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Chest opener on an exercise ball

- Lie on your back on an exercise ball. Your shoulder blades, neck and head should be on the top of the ball, with your back extended, feet flat on the floor, and knees flexed at 90-degrees.

- Begin the stretch by opening up your arms and letting them fall to the side of the ball. Make sure you’re looking up at the ceiling.

- Hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

Injuries

The abdomen can be injured in many ways. The abdomen alone may be injured or injuries elsewhere in the body may also occur. Injuries can be relatively mild or very severe.Blunt trauma may involve a direct blow (for example, a kick), impact with an object (for example, a fall onto bicycle handlebars), or a sudden decrease in speed (for example, a fall from a height or a motor vehicle crash). The spleen and liver are the two most commonly injured organs. Hollow organs are less likely to be injured.

Penetrating injuries occur when an object breaks the skin (for example, as a result of a gunshot or a stabbing). Some penetrating injuries involve only the fat and muscles under the skin. These penetrating injuries are much less concerning than those that enter the abdominal cavity. Gunshots that enter the abdominal cavity almost always cause significant damage. However, stab wounds that enter the abdominal cavity do not always damage organs or blood vessels. Sometimes, a penetrating injury involves both the chest and the upper part of the abdomen. For example a downward stab wound to the lower chest may go through the diaphragm into the stomach, spleen, or liver.

Blunt or penetrating injuries may cut or rupture abdominal organs and/or blood vessels. Blunt injury may cause blood to collect inside the structure of a solid organ (for example, the liver) or in the wall of a hollow organ (such as the small intestine). Such collections of blood are called hematomas. Uncontained bleeding into the abdominal cavity, in the space surrounding the organs, is called hemoperitoneum.

Cuts and tears begin bleeding immediately. Bleeding may be minimal and cause few problems. More serious injuries may cause massive bleeding with shock and sometimes death. Bleeding from abdominal injury is mostly internal (within the abdominal cavity). When there is a penetrating injury, a small amount of external bleeding may occur through the wound. When a hollow organ is injured, the contents of the organ (for example, stomach acid, stool, or urine) may enter the abdominal cavity and cause irritation and inflammation (peritonitis).

Source