About the chest muscles

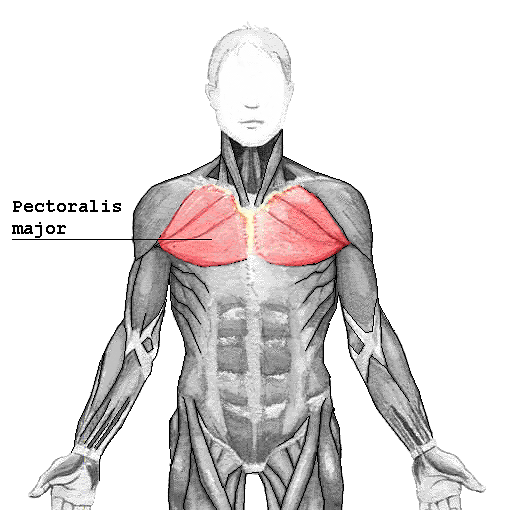

Pectoralis Major

The pectoralis major has four actions which are primarily responsible for movement of the shoulder joint.[7] The first action is flexion of the humerus, as in throwing a ball underhand, and in lifting a child. Secondly, it adducts the humerus, as when flapping the arms. Thirdly, it rotates the humerus medially, as occurs when arm-wrestling. Fourthly the pectoralis major is also responsible for keeping the arm attached to the trunk of the body.[7][8] It has two different parts which are responsible for different actions. The clavicular part is close to the deltoid muscle and contributes to flexion, horizontal adduction, and inward rotation of the humerus. When at an approximately 110 degree angle,[citation needed] it contributes to adduction of the humerus. The sternocostal part is antagonistic to the clavicular part contributing to downward and forward movement of the arm and inward rotation when accompanied by adduction. The sternal fibers can also contribute to extension, but not beyond anatomical position.

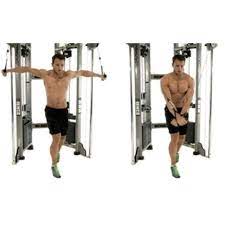

Hypertrophy of the pectoralis major increases functionality. Maximal activation of the pectoralis major occurs in the transverse plane through pressing motions. Both multi-joint and single-joint exercises induce pectoralis major hypertrophy. A combination of both single-joint and multi-joint exercises will result in a maximum hypertrophic response. [Aesthetic contours of regions in the muscle may be specifically-addressed (“targeted”) by specific exercises; for instance, “plating” or “stitching” of the pectoralis major —towards the center of the sternum —-may be targeted by a wider hand position.] The pectoralis major can be targeted from numerous training angles along the sternum and clavicle.[10] Exercises that include horizontal adduction and elbow extensions such as the barbell bench press, dumbbell bench press, and machine bench press induce high activation of the pectoralis major in the sternocostal region. Heavy loads are strongly correlated with pectoralis major activation.[11]

Source

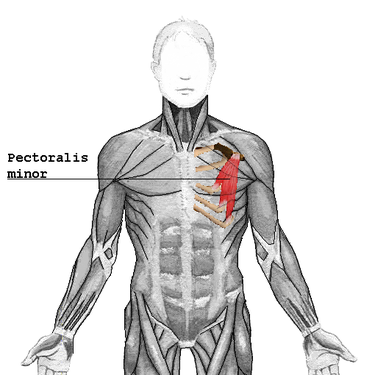

Pectoralis Minor

The pectoralis minor depresses the point of the shoulder, drawing the scapula superior, towards the thorax, and throwing its inferior angle posteriorly. Source

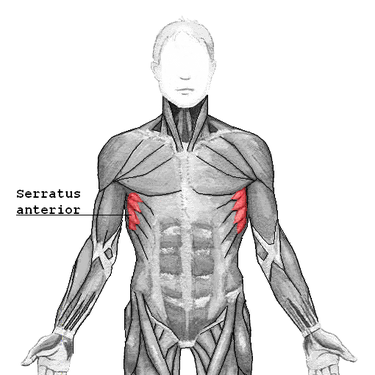

Serratus Anterior

The serratus anterior is a muscle that originates on the surface of the 1st to 8th ribs at the side of the chest and inserts along the entire anterior length of the medial border of the scapula. The serratus anterior acts to pull the scapula forward around the thorax. The muscle is named from Latin: serrare = to saw, referring to the shape, anterior = on the front side of the body.

The Serratus Anterior's funtion is to pull the scapula forward around the thorax, which is essential for anteversion of the arm. As such, the muscle is an antagonist to the rhomboids. However, when the inferior and superior parts act together, they keep the scapula pressed against the thorax together with the rhomboids and therefore these parts also act as synergists to the rhomboids. The inferior part can pull the lower end of the scapula laterally and forward and thus rotates the scapula to make elevation of the arm possible. Additionally, all three parts can lift the ribs when the shoulder girdle is fixed, and thus assist in respiration.

The serratus anterior is occasionally called the "big swing muscle" or "boxer's muscle" because it is largely responsible for the protraction of the scapula — that is, the pulling of the scapula forward and around the rib cage that occurs when someone throws a punch. The serratus anterior also plays an important role in the upward rotation of the scapula, such as when lifting a weight overhead. It performs this in sync with the upper and lower fibers of the trapezius.

Source

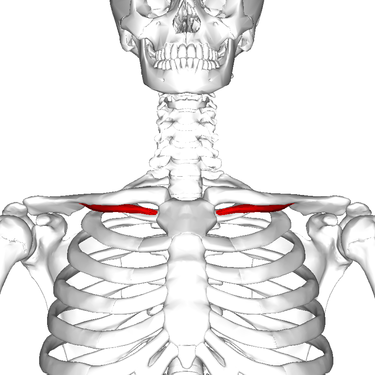

Subclavius

The subclavius is a small triangular muscle, placed between the clavicle and the first rib.[1] Along with the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles, the subclavius muscle makes up the anterior axioappendicular muscles, also known as anterior wall of the axilla. It depresses the lateral clavicle, acts to stabilize the clavicle while the shoulder moves the arm. It also raises the first rib while lowering the clavicle during breathing. The subclavius protects the underlying brachial plexus and subclavian vessels from a broken clavicle - the most frequently broken long bone.

Source

Exercises

Stretches

- Behind-the-back Elbow-to-elbow Grip

- Seated or standing, begin with arms hanging by your sides and shoulders pressed down away from your ears.

- Gently squeeze your shoulder blades together and broaden the chest. Bring the arms behind the back and grip elbow to elbow.

- Above-the-head Chest Stretch

- Seated or standing, interlock your fingers, bend your elbows and raise your arms above your head.

- Gently squeeze your shoulder blades together and move your elbows and hands backward.

- Vary the height of your hands to emphasize shoulders and/or chest (hands behind head, hands on top of head, hand a few inches above head).

- Bent-arm Wall Stretch

- Assume a split stance, Right leg in the front and left leg in the back, at the end of a wall or in a doorway.

- Bring the left arm up to shoulder height and position the palm and inside of the arm on the wall surface or doorway. Your arm should look like a goal post.

- Gently press the chest through the open space to feel the stretch.

- Moving the arm higher or lower will allow you to stretch various sections of the chest.

- Repeat on the other side.

- Extended Child’s Pose on Fingertips

- Kneel on the floor. Touch your big toes together and sit on your heels; next, separate your knees about as wide as your hips.

- Bend forward from the hips and walk your hands out as far in front of you as possible. With the arms extended and palms facing down, come up onto the fingertips as if you have a ball underneath your palms and melt the chest toward the floor.

- Side Lying Parallel Arm Chest Stretch

- Lying prone on your stomach, bring both arms out to the sides, palms facing down, to create the letter T.

- Start to roll onto your right side by pushing yourself with your left hand. Lift the left leg, bend the knee and place the left foot behind you on the floor for stability. Rest your right temple on the floor.

- Keep the left hand on the floor for balance. For an extra stretch, lift the left hand up toward the ceiling.

- Repeat on the other side.

Injuries

Tears of the pectoralis major are rare and typically affect otherwise healthy individuals. This type of injury is known to affect the athletic population, namely in high-impact contact sports such as powerlifting, and may result in pain, weakness, and disability. Most lesions are located at the musculotendinous junction and result from violent, eccentric contraction of the muscle, such as during bench press.[12] A less frequent rupture site is the muscle belly, usually as a result of a direct blow. In developed countries, most lesions occur in male athletes, especially those practicing contact sports and weight-lifting (particularly during a bench press maneuver). Women are less susceptible to these tears because of larger tendon-to-muscle diameter, greater muscular elasticity, and less energetic injuries.[13] The injury is characterized by sudden and acute pain in the chest wall and shoulder area, bruising and loss of strength of the muscle. High grade partial or full thickness tears warrant surgical repair as the preferred treatment if function is to be preserved, particularly in the athletic population.

Acting fast, obtaining the correct diagnoses, and getting the surgical repair as soon as possible is a key to successful recovery. Waiting can cause the acute injury to become chronic and chances of success is greatly diminished as a result. After surgery, the impacted arm is then immobilized with a sling for about six to eight weeks to minimize and avoid movement of the arm and potentially re-rupturing the surgery site. About two months after the surgery, physical therapy is typically introduced for about six months, after which point strengthening of the muscle is needed to achieve good results. Most patients are able to return to activity after six months to a year following surgery with high patient satisfaction and slightly reduced strength compared to pre-injury.[12] Both US[14] and MRI[15] are useful to confirm the diagnosis, location and extent of a tear, though the first may be more cost-effective in experienced hands.

Source